Forests and the Global Forest Carbon Balance: A Comparative Assessment of Major Forest Regions and an Australian Review

Including a significant update on Australian forests, what you can do and the importance of MANA's natural mindfulness program

Overview

Recent syntheses indicate that, taken together, the world's forests remain a net carbon sink, removing approximately 3.5 ± 0.4 Gt C per year from the atmosphere (Pan et al., 2011; Friedlingstein et al., 2022). However, this global sink is increasingly maintained by temperate forests and portions of the boreal zone, while tropical forests—including the Amazon, Congo Basin, and Southeast Asia—have weakened significantly and, in several regions, now function as net carbon sources due to deforestation, degradation, fire, and climate-driven stress (Baccini et al., 2017; Hubau et al., 2020; Gatti et al., 2021).

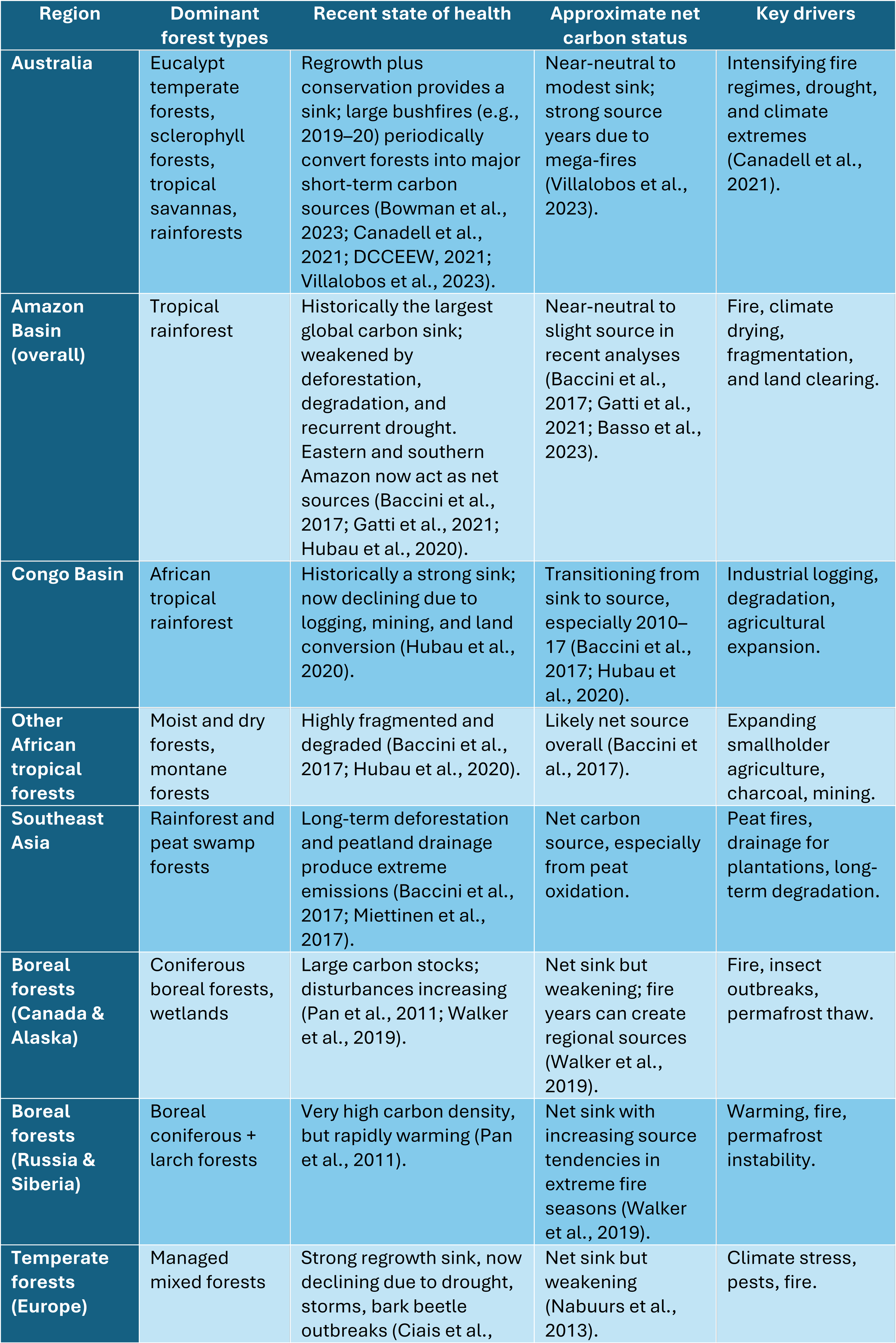

Below is a qualitative summary by major forest region, focusing on the last decade. Exact flux estimates differ across measurement approaches (atmospheric inversion, biometric data, satellite biomass change), so categories are presented in broad, policy-relevant terms.

Globally, forests remain a net carbon sink, removing approximately 2–3 Gt C per year from the atmosphere. However, this sink is weakening and increasingly reliant on temperate and some boreal regions, while tropical forests have shifted toward near-neutral or net sources due to deforestation, degradation, fire, and climate stress (Baccini et al., 2017; Hubau et al., 2020; Pan et al., 2011; Villalobos et al., 2023).

Australia is presented first, followed by other major forest regions.

Table 1. Major Forest Regions, Condition, and Approximate Carbon Balance (Last Decade)

Synthesis

Across all regions, a clear pattern emerges:

Temperate forests provide the strongest and most reliable sinks.

Boreal forests remain large sinks but are destabilising due to warming and fires.

Tropical forests, once the backbone of the global forest sink, are increasingly near-neutral or net sources, primarily because of human-driven degradation and climate stress.

Australia mirrors global instability: forests remain potential sinks but can flip into major short-term carbon sources during extreme bushfire years.

How Australian Forests Have Changed Over 100, 50, and 20 Years

Australian forests have never been static. They are living systems shaped by deep-time fire regimes, the long stewardship of First Nations peoples, and the pressures of colonisation and modern industry. When we look back across the last century — first through a 100-year window, then 50, then 20 — the story becomes unmistakably clear: the forces acting on forests have intensified, accelerated, and converged. Clearing dominated the early period, climate stress defined the middle, and in the last two decades climate change has become the central organising force of forest transformation.

What follows is a narrative of this unfolding trajectory.

A Century of Change (1925–2025)

A hundred years ago, the great project shaping forests was clearing. Across the southern states, vast expanses of woodland, mallee, and open forest were bulldozed or ringbarked to create a pastoral nation (Bradshaw, 2012). Entire ecosystems were simplified into sheep paddocks and wheat belts. Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, and Tasmania all lost much of their lowland and fertile forest cover during this era.

Industrial forestry accelerated in the mid-century. Logging became mechanised; roads pushed deeper into forests; plantations of pine and fast-growing eucalypts were established across the country (ABARES, 2022). With clearing and fragmentation came the slow unravelling of biodiversity. Australia — already rich in fire-adapted species — began losing mammals at a rate unmatched anywhere else (Woinarski et al., 2015).

During this period, fire remained a familiar presence but rarely escalated into the extreme, climate-driven events we recognise today. The atmosphere was cooler, drought cycles were less severe, and forests were generally more resilient (Bowman et al., 2011). In hindsight, it was a more stable era — though already environmentally compromised by clearing.

Fifty Years of Transformation (1975–2025)

By the mid-1970s, the ecological mood had shifted. Many of the worst excesses of clearing were beginning to slow, especially in Victoria and New South Wales, where new conservation laws emerged. Yet Queensland — twice the size of the next largest state — continued to clear at globally significant levels, with destructive peaks in the 1980s, 1990s, and again after 2013 (Evans, 2016). The patchwork of forest protection across Australia depended heavily on political cycles.

At the same time, the climate itself was beginning to change. By the 1990s:

droughts grew longer,

heatwaves intensified, and

dieback events appeared in regions historically considered stable (Hughes et al., 2017).

Forests were no longer shaped only by chainsaws and bulldozers; they were being altered by rising temperatures and shifting rainfall patterns. Fires became more intense and the fire season gradually lengthened. What had once been the occasional severe season was becoming a new baseline.

Carbon dynamics were shifting too. Previously reliable sinks — such as tall wet forests — began showing signs of stress, their carbon uptake eroded by drought and increasingly damaging fires (Canadell et al., 2021).

This 50-year window reads like a long inhale before the storm.

Twenty Years of Turbulence (2005–2025)

The last two decades have been unlike anything recorded before. The combination of extreme heat, deep drought, and abundant dry fuel culminated in a new phenomenon: the Australian megafire.

The 2019–20 Black Summer fires burned over 24 million hectares, including one-fifth of the continent's temperate broadleaf forests — an event unprecedented not only historically but in the paleo-fire record stretching back millennia (Boer et al., 2020; Nolan et al., 2020).

Forests that once acted as massive carbon sinks were transformed almost overnight into enormous carbon sources, releasing an estimated 830 million tonnes of CO₂-e — more than Australia's industrial emissions for that year (Bowman et al., 2023).

In the aftermath, some forests began their slow recuperation. Others faced more existential challenges. Alpine ash and mountain ash forests, which need long intervals between fires to regenerate, now face the risk of recruitment failure after repeated burns. Even rainforests — ecosystems typically too wet to burn — experienced unprecedented fire incursion in the Gondwana regions of NSW and Queensland.

Meanwhile, climate-induced dieback expanded rapidly. Eucalypt crown decline, drought mortality, insect outbreaks, and soil moisture collapse were reported across the continent. In southwest WA, some forest systems show signs of crossing critical climate thresholds (Matusick et al., 2013).

Policy responses have begun to shift — with native forest logging ending in Victoria (2023) and Western Australia (2024) — yet national-scale biodiversity and climate frameworks remain underdeveloped and underfunded.

In these 20 years, the fingerprint of climate change has become unmistakable. Forests are not just experiencing individual extreme events; they are entering a new ecological regime.

The Trajectory in One Arc

Across these three timescales, a pattern emerges:

100 years: A continent reshaped by clearing, land conversion, and resource extraction.

50 years: Ecological decline meets emerging climate destabilisation.

20 years: Climate change becomes the dominant ecological force — expressed through megafires, widespread dieback, and carbon sink instability.

Australia's forests have moved from being cut down, to being stressed, to being climate-altered at a foundational level.

The next two decades will be decisive: whether forests adapt and recover, or whether they shift into permanently altered states dominated by fire, drought, and reduced carbon storage.

Prediction: In Australia, What Will Remain Undisturbed by 2030?

By 2030, Australia's remaining intact forests will be shaped primarily by the intensifying effects of a warming climate. Because 2030 is only one climate cycle away, the projections rely more on current trajectories than long-term climate modelling. Even so, Australia is already in a period of rapid ecological disruption, meaning substantial shifts in what qualifies as "undisturbed forest" are likely within this decade.

Climate as the immediate pressure

Extreme heat, prolonged drought periods, and record levels of fuel dryness have already become more common across southern and eastern Australia (Harris & Lucas, 2019; Canadell et al., 2021). These trends are expected to intensify further by 2030 under all emissions scenarios.

The 2019–20 Black Summer fires demonstrated that ecosystems once considered buffered—cool temperate rainforests, Gondwanan relic systems, and alpine ash forests—are increasingly vulnerable (Nolan et al., 2020; Ward et al., 2020). Thus, the key determinant of "undisturbed forest" over the next decade will be the frequency of severe fire seasons, not long-term land use.

Fire may remove 10–20% of remaining intact forest even before 2030

Fire-weather modelling indicates that the risk of severe fire seasons—once expected every 10–15 years—is now closer to every 3–5 years in southeastern Australia (Clarke et al., 2022; IPCC, 2021).

Two or three additional severe fire seasons before 2030 would be enough to affect:

long-unburnt mountain ash and alpine ash stands,

flammable wet sclerophyll edges,

eucalypt forests in southeast Queensland and northern NSW,

pockets of rainforest already impacted in 2019–20.

While a single fire does not destroy ecological integrity, repeated burns within short intervals do. Many obligate-seeding species cannot recover if fires recur within 8–20 years (Bowman et al., 2020). Therefore, even without further land clearing, climate-driven fire regimes will likely erode a significant proportion of Australia's existing intact forest by 2030.

Governance remains decisive, even in a short timeframe

Because 2030 is close, governance choices over the next five years carry disproportionately high weight.

Measures that could preserve significant intact forest include:

ending native forest logging nationwide,

immediate halting of Queensland broadscale land clearing,

rapid reinvestment in Indigenous-led cultural burning (Ens et al., 2015),

establishing large, connected no-go conservation corridors,

reducing ignition risks around high-value forests.

Without such interventions, the interaction between climate and fragmentation will accelerate disturbance.

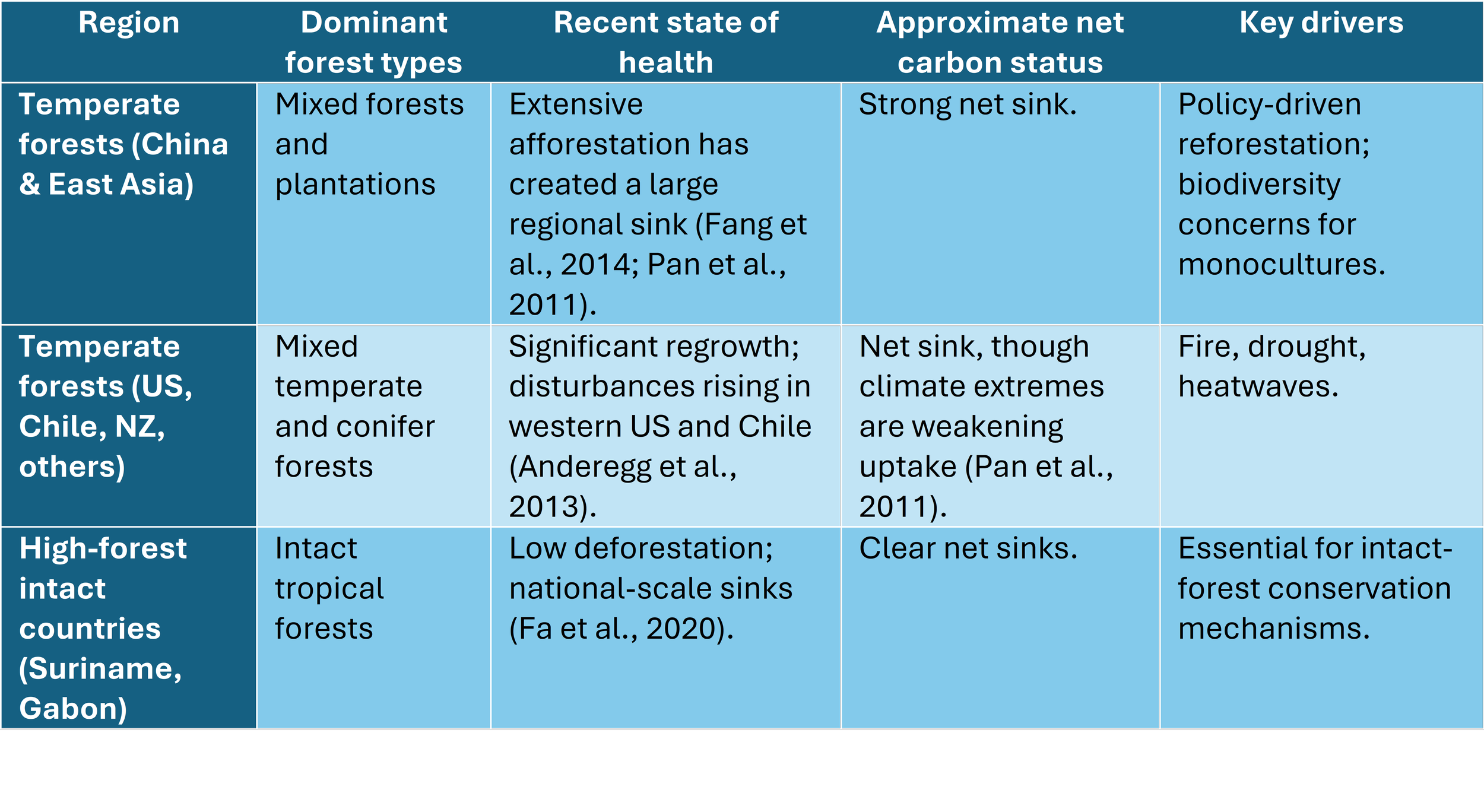

What is likely by 2030?

Given current climate trends, fire-weather projections, and the legacy of the 2019–20 megafires, the following scenario is the best-supported near-term assessment:

By 2030, only 6–8% of Australia's forests may remain ecologically intact and genuinely undisturbed.

This incorporates the expectation of at least one additional severe fire season and ongoing clearing in parts of Queensland.

In a strong conservation and mitigation scenario, intact forest might remain at 8–10%.

Under business-as-usual, with continued clearing and partial fire management, 6–8% is the most probable range.

In a pessimistic scenario—severe drought, extreme fire weather, and weak governance—intact forest could fall to 5% or less by 2030.

Where the last intact forests will persist

By 2030, the remaining undisturbed forests are likely to be concentrated in:

remote monsoonal woodlands of Arnhem Land and Cape York,

southwest wilderness areas of Tasmania,

selected enclaves of the Wet Tropics that avoid major cyclone-fire interactions,

rugged high-country areas: escarpments, deep gorges, steep terrain with broken fuel loads.

These sites are buffered mainly by geography, low accessibility, or continuous Indigenous management, not by climatic safety.

The deeper implication

Australia's intact forests are undergoing a rapid near-term transformation. Disturbance—particularly climate-driven fire—is becoming the ecological baseline. By 2030, the definition of "undisturbed forest" will be constrained not only in area but in meaning, as ecosystems shift into new states shaped by hotter, drier, more volatile conditions.

What remains unburnt and unfragmented by the end of this decade will reflect urgent choices made now—governance, cultural burning revival, emissions pathways, and land-clearing policy—more than any long-term future climatic target.

Projected Intact Forest Remaining by 2030

What Individuals, Families, and Communities Can Do

Despite the scale of global forest loss, the research is clear: meaningful action does not rely solely on governments or corporations. Forest stability is shaped by countless small decisions — what we buy, how we live, what we eat, how we vote, and how we care for the places we inhabit (Otto et al., 2020; Griscom et al., 2017). These actions ripple outward through families and communities, creating powerful social tipping points that support ecological renewal (Ostrom, 2010).

Below is a narrative guide showing how individuals, families, and communities can help protect forests and strengthen carbon sinks.

1. What an Individual Can Do

Every person carries a kind of "ecological signature" — not a moral burden, but a pattern of daily practices that either ease or intensify pressure on the world's forests. (Note: this section is referenced separately.)

A. Rethinking consumption

Local people do not cause most tropical deforestation; it is caused by distant demand for beef, soy, palm oil, and timber (Pendrill et al., 2019). Each time we reach for a product, we cast a tiny vote in a global system. Individuals can meaningfully reduce their ecological footprint by choosing:

fewer high-deforestation foods,

certified timber and paper (FSC, 2021),

and products free from palm oil linked to forest destruction (Carlson et al., 2018).

These small choices accumulate.

B. Eating with awareness

Diet is a quiet but powerful driver of forest loss. Studies show that reducing red meat consumption significantly lowers global land pressure, allowing ecosystems to recover (Tilman & Clark, 2014).

Moving toward plant-forward meals — not perfection, but steady shifts — protects forests half a world away.

C. Supporting the guardians of intact forests

Donations, memberships, and monthly contributions to Indigenous land-protection groups, tropical forest NGOs, or climate–forest alliances strengthen the most effective defenders of global carbon stores (Fa et al., 2020; Garnett et al., 2018).

D. Aligning money with values

Our banking and superannuation choices quietly shape the world. Redirecting personal finances away from fossil fuels and industrial agriculture reduces the financial oxygen that fuels deforestation (Newell et al., 2021).

E. Reducing personal carbon emissions

Forests absorb our emissions. Every tonne we don't emit is a tonne forests don't need to cope with. Shifting to renewable energy, improving household efficiency, and reducing air travel have disproportionately large climate impacts (Wynes & Nicholas, 2017).

F. Advocacy as ecological care

One informed, polite email to a local MP or council can have more influence than most people ever realise. Individual political participation is strongly linked with environmental policy uptake (Otto et al., 2020).

Advocacy is not activism alone — it is care scaled up.

2. What a Family or Household Can Do

Families form miniature cultures. They shape habits, food patterns, and values — especially in children, who, research shows, develop lifelong ecological orientations through early nature connection (Barrera-Hernández et al., 2020).

A. Creating a low-waste household culture

Reducing packaging, composting, and buying less paper all decrease demand for forest-derived products (Schyns et al., 2019). Small shifts in routine create a sense of shared stewardship.

B. Changing the family table

Even a few plant-based meals per week can significantly reduce a household's hidden forest footprint (Springmann et al., 2018).

Cooking together, trying new recipes, or exploring local food networks turns climate action into connection.

C. Transforming the home environment

Energy efficiency — solar panels, insulation, heat pumps — not only lowers bills but also cuts household carbon emissions (IPCC, 2022). Families can become living demonstrations of what low-carbon living looks like, inspiring neighbours.

D. Caring for land, even small land

A balcony garden, a courtyard of native plants, or a regenerating patch of rural forest all build what scientists call "ecological micro-refugia" — tiny pockets of habitat that support biodiversity (Aronson et al., 2017).

If a family owns land, restoration becomes a generational gift.

E. Teaching ecological literacy

Children who play in nature, tend gardens, or learn simple ecological principles grow into adults who protect the natural world (Barrera-Hernández et al., 2020).

Families teach the future.

3. What a Community Can Do

Research consistently shows that the greatest ecological change emerges not from isolated individuals but from communities acting together (Ostrom, 2010). When a community shifts, norms shift — and norms drive behaviour at scale.

A. Local councils respond to collective voices

Communities can pressure councils to protect remnant forest patches, restore riparian corridors, strengthen biodiversity plans, regulate clearing, and invest in climate adaptation. This local, polycentric governance is highly effective (Ostrom, 2010).

B. Collective restoration creates measurable carbon sinks

Tree-planting events, creek-line regeneration, fire-sensitive habitat restoration, and community urban-forest programs all contribute to measurable carbon sequestration and ecological resilience (Griscom et al., 2017).

C. Supporting Indigenous leadership

Indigenous land-management — from cultural burning to forest guardianship — produces some of the world's best conservation outcomes (Garnett et al., 2018; Fa et al., 2020).

Communities can partner, fund, and amplify this work.

D. Building resilient local food systems

Local agroecology reduces dependence on imported forest-risk commodities and strengthens regional resilience (Rajão et al., 2020).

Community-supported agriculture, farmers' markets, and regenerative grazing collectives are powerful tools.

E. Community procurement and divestment

When a council, school, or community group switches to certified timber or ethical banking, the ripple effects are far larger than any one household (FSC, 2021; Newell et al., 2021).

F. Building a shared ecological culture

Nature walks, festivals, workshops, community climate groups, and forest-connection days help shift "what is normal." Social tipping-point research shows that once 20–25% of a community adopts a new norm, change accelerates rapidly (Otto et al., 2020).

Why This Matters

None of these actions alone will "save the forests." But together — individuals acting with intention, families modelling care, and communities organising with purpose — they create the social momentum that enables governments, markets, and institutions to act at scale.

Climate and forest protection emerge from the inside out:

inner awareness → household practice → community strength → political transformation.

References

ABARES. (2022). Australian plantation statistics 2022. Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences.

Anderegg, W. R. L., Kane, J. M., & Anderegg, L. D. L. (2013). Consequences of widespread tree mortality triggered by drought and temperature stress. Nature Climate Change, 3(1), 30–36. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1635

Baccini, A., Walker, W., Carvalho, L., Farina, M., Houghton, R. A., & Draper, F. C. (2017). Tropical forests are a net carbon source based on aboveground measurements of gain and loss. Science, 358(6360), 230–234.

Basso, L. S., Gloor, M., Miller, J. B., Gatti, L. V., Domingues, L. G., Correia, C. S. C., Cassol, H. L. G., et al. (2023). Atmospheric CO₂ inversion reveals the Amazon as a minor net source of carbon to the atmosphere. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 23(15), 9685–9708.

Boer, M. M., et al. (2020). Unprecedented burn area of Australian mega-fires. Nature Climate Change, 10, 171–172.

Bowman, D. M. J. S., Williamson, G. J., Prior, L. D., & Murphy, B. P. (2020). The severity and extent of the Australia 2019–20 megafires are not unprecedented. Nature Climate Change, 10(6), 339–340. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0741-0

Bowman, D. M. J. S., Williamson, G. J., Ndalila, M. N., & Prior, L. D. (2023). How natural and anthropogenic landscape fires emissions are reported in Australia's greenhouse gas accounts. Carbon Balance and Management, 18, 21.

Bowman, D. M. J. S., et al. (2011). The human dimension of fire regimes. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 276, 3631–3639.

Bradshaw, C. J. A. (2012). Little left to lose: Deforestation and forest degradation in Australia. Biological Conservation, 151, 113–122.

Canadell, J. G., Meyer, C. P., Cook, G. D., Dowdy, A., Briggs, P. R., & McCaw, L. (2021). Multi-decadal increase of forest fire weather and fire extent in Australia. Environmental Research Letters, 16(8), 084047.

Canadell, J. G., Meyer, C. P., Cook, G. D., Dowdy, A., Briggs, P. R., Knauer, J., Pepler, A., et al. (2021). Multi-decadal increase of forest burned area in Australia is linked to climate change. Nature Communications, 12, 6921.

Ciais, P., Schelhaas, M. J., Zaehle, S., Piao, S. L., Cescatti, A., Liski, J., Luyssaert, S., et al. (2008). Carbon accumulation in European forests. Nature Geoscience, 1(7), 425–429.

Clarke, H., Tran, B. N., Boer, M. M., Price, O., Kenny, B., & Bradstock, R. A. (2022). Evidence for increasing extreme fire weather in southeast Australia. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 127(4), e2021JD035710.

DCCEEW. (2023). State of the Environment Report 2023. Australian Government.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water. (2021). Estimating greenhouse gas emissions from bushfires in Australia's temperate forests: Focus on 2019–20. Australian Government.

Ens, E. J., Walsh, F. J., & Clarke, P. A. (2015). Indigenous biocultural knowledge in ecosystem science and management: Review and insight from Australia. Biological Conservation, 181, 133–149.

Evans, M. C. (2016). Deforestation in Australia: Drivers, trends, and policy responses. Pacific Conservation Biology, 22, 324–333.

Fa, J. E., Watson, J. E. M., Leiper, I., Potapov, P., Evans, T. D., Burgess, N. D., Molnár, Z., et al. (2020). Importance of Indigenous Peoples' lands for the conservation of intact forest landscapes. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 18(3), 135–140.

Fang, J., Yu, G., Liu, L., Hu, S., & Chapin, F. S., III. (2014). Climate change, human impacts, and carbon sequestration in China. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(49), 17331–17336.

Gatti, L. V., Basso, L. S., Miller, J. B., Gloor, M., Gatti Domingues, L., Cassol, H. L. G., Tejada, G., et al. (2021). Amazonia as a carbon source linked to deforestation and climate change. Nature, 595(7867), 388–393.

Harris, S., & Lucas, C. (2019). Understanding the variability of Australian fire weather. Climatic Change, 156, 381–398.

Harris, S., & Lucas, C. (2019). Understanding the variability of Australian fire weather between 1973 and 2017. PLOS ONE, 14(9), e0222328.

Hubau, W., Lewis, S. L., Phillips, O. L., Affum-Baffoe, K., Beeckman, H., Cuní-Sanchez, A., Daniels, A. K., et al. (2020). Asynchronous carbon sink saturation in African and Amazonian tropical forests. Nature, 579(7797), 80–87.

Hughes, L., et al. (2017). Climate Change and Australia's Forests. CSIRO.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2021). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Cambridge University Press.

Matusick, G., et al. (2013). Sudden forest decline from drought in southwest Australia. Forest Ecology and Management, 306, 156–166.

Miettinen, J., Shi, C., & Liew, S. C. (2017). Land cover distribution in the peatlands of Peninsular Malaysia, Sumatra and Borneo in 2015 with changes since 1990. Global Ecology and Conservation, 6, 67–78.

Nabuurs, G.-J., Lindner, M., Verkerk, P. J., Gunia, K., Deda, P., Michalak, R., & Grassi, G. (2013). First signs of carbon sink saturation in European forest biomass. Nature Climate Change, 3(9), 792–796.

Nolan, R. H., Boer, M. M., Collins, L., Resco de Dios, V., Clarke, H., Jenkins, M., Kenny, B., & Bradstock, R. A. (2020). Causes and consequences of eastern Australia's 2019–20 season of mega-fires. Global Change Biology, 26(3), 1039–1041.

Pan, Y., Birdsey, R. A., Fang, J., Houghton, R., Kauppi, P. E., Kurz, W. A., Phillips, O. L., et al. (2011). A large and persistent carbon sink in the world's forests. Science, 333(6045), 988–993.

Villalobos, Y., Haverd, V., Briggs, P. R., Canadell, J. G., Meyer, C. P., Roxburgh, S. H., Houlton, B. Z., et al. (2023). A comprehensive assessment of anthropogenic and natural sources and sinks of CO₂ for Australasia, 2010–2019. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 37(10), e2023GB007702.

Walker, X. J., Baltzer, J. L., Cumming, S. G., Day, N. J., Ebert, C., Goetz, S., Johnstone, J. F., et al. (2019). Increasing wildfires threaten historic carbon sink of boreal forest soils. Nature, 572(7770), 520–523.

Ward, M., Tulloch, A. I. T., Radford, J. Q., Williams, B. A., Reside, A. E., MacDonald, S. L., Mayfield, H. J., Maron, M., Bennett, A. F., & Possingham, H. (2020). Impact of 2019–2020 mega-fires on Australian wildlife habitat. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 4(10), 1321–1326.

Woinarski, J. C. Z., et al. (2015). Ongoing unraveling of Australia's mammal fauna. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112, 4531–4540.

References to: "What we can do."

Aronson, J., Blignaut, J. N., Milton, S. J., Le Maitre, D., Esler, K. J., Limouzin, A., ... & Lederer, N. (2017). Restoring natural capital: Science, business, and practice. Island Press.

Baccini, A., Walker, W., Carvalho, L., Farina, M., Houghton, R. A., & Draper, F. C. (2017). Tropical forests are a net carbon source based on aboveground measurements of gain and loss. Science, 358(6360), 230–234.

Barrera-Hernández, L. F., Sotelo-Castillo, M. A., Echeverría-Castro, S. B., & Tapia-Fonllem, C. O. (2020). Connectedness to nature: Its impact on sustainable behaviors and happiness in children. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 276.

Carlson, K. M., Heilmayr, R., Gibbs, H. K., Noojipady, P., Burns, D. N., Morton, D. C., ... & Kremen, C. (2018). Effect of oil palm sustainability certification on deforestation and fire in Indonesia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(1), 121–126.

Fa, J. E., Watson, J. E. M., Leiper, I., Potapov, P., Evans, T. D., Burgess, N. D., ... & Garnett, S. T. (2020). Importance of Indigenous Peoples' lands for the conservation of intact forest landscapes. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 18(3), 135–140.

FSC. (2021). Global Market Survey. Forest Stewardship Council.

Friedlingstein, P., Jones, M. W., O'Sullivan, M., Andrew, R. M., Bakker, D., Hauck, J., ... & Peters, G. P. (2022). Global carbon budget 2022. Earth System Science Data, 14, 4811–4906.

Garnett, S. T., Burgess, N. D., Fa, J. E., Fernández-Llamazares, Á., Molnár, Z., Robinson, C. J., ... & Watson, J. E. M. (2018). A spatial overview of the global importance of Indigenous lands for conservation. Nature Sustainability, 1(7), 369–374.

Gatti, L. V., Basso, L. S., Miller, J. B., Gloor, M., Gatti Domingues, L., Cassol, H. L. G., ... & Aragão, L. E. O. C. (2021). Amazonia as a carbon source linked to deforestation and climate change. Nature, 595, 388–393.

Griscom, B. W., Adams, J., Ellis, P. W., Houghton, R. A., Lomax, G., Miteva, D. A., ... & Fargione, J. (2017). Natural climate solutions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(44), 11645–11650.

IPCC. (2022). Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press.

Newell, P., Fankhauser, S., & Jackson, T. (2021). Net zero for finance? Nature Climate Change, 11, 394–396.

Ojala, M. (2018). Eco-anxiety. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 9(6), e560.

Ostrom, E. (2010). Polycentric systems for coping with collective action and global environmental change. Global Environmental Change, 20(4), 550–557.

Otto, I. M., Donges, J. F., Cremades, R., Bhowmik, A., Hewitt, R. J., Lucht, W., ... & Schellnhuber, H. J. (2020). Social tipping dynamics for stabilising Earth's climate. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(5), 2354–2365.

Pendrill, F., Persson, U. M., Godar, J., & Kastner, T. (2019). Deforestation displaced: Trade in forest-risk commodities and the prospects for a global forest transition. Environmental Research Letters, 14(5), 055003.

Rajão, R., Soares-Filho, B., Nunes, F., Börner, J., Machado, L., Assis, D., ... & Figueira, D. (2020). The rotten apples of Brazil's agribusiness. Science, 369(6501), 246–248.

Schyns, J. F., Booij, M. J., & Hoekstra, A. Y. (2019). The water footprint of wood for lumber, pulp, paper, fuel and firewood. Environmental Research Letters, 14(12), 124017.

Springmann, M., Clark, M., Mason-D'Croz, D., Wiebe, K., Bodirsky, B. L., Lassaletta, L., ... & Willett, W. (2018). Options for keeping the food system within environmental limits. Nature, 562(7728), 519–525.

Tilman, D., & Clark, M. (2014). Global diets link environmental sustainability and human health. Nature, 515(7528), 518–522.

Wynes, S., & Nicholas, K. A. (2017). The climate mitigation gap: Education and government recommendations miss the most effective individual actions. Environmental Research Letters, 12(7), 074024.