Science Explainer on Radiative Forcing

Radiative forcing is the central physical driver of global warming, yet it remains one of the least understood concepts in public discussion. It describes the extent to which the Earth’s energy balance is being pushed out of equilibrium by greenhouse gases and other human activities. When radiative forcing rises, the planet accumulates heat; when it falls, the planet cools. This additional heat is measured in watts per square metre (W/m²), a unit describing how much extra energy is added to every square metre of the Earth’s surface. One watt corresponds to one joule of energy per second, meaning even small increases in forcing compound into vast amounts of stored heat over time.

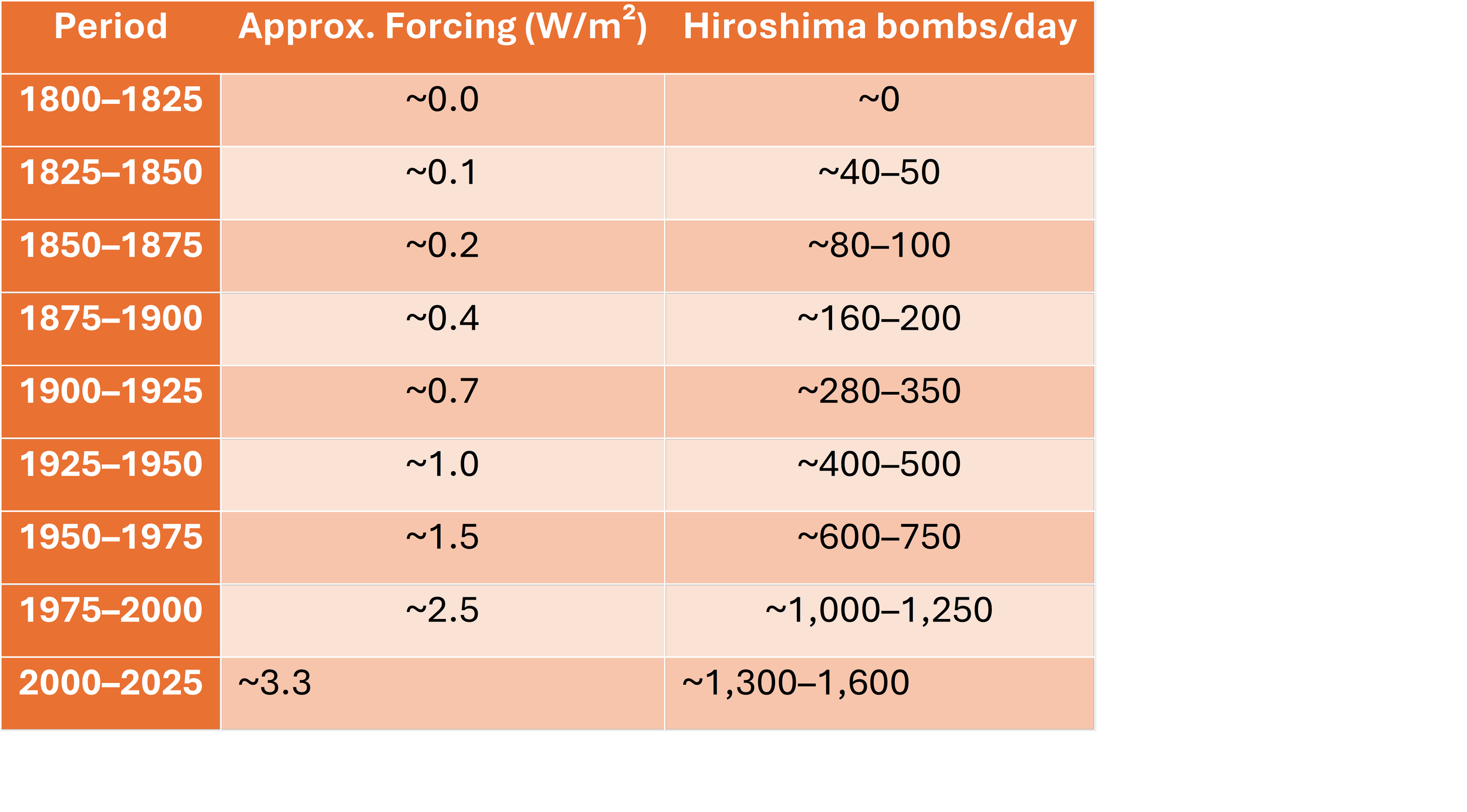

To clarify how radiative forcing has changed across the industrial era, the following table summarises approximate values at 25-year intervals from 1800 to the present. These estimates draw from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report, the NASA GISS forcing datasets, NOAA’s Global Greenhouse Gas Reference Network, and the long-term reconstruction work of Meinshausen and colleagues. The Hiroshima-bomb energy equivalence is derived from Trenberth and Fasullo’s quantification of Earth’s heat imbalance and Glasstone and Dolan’s established figure for the energy released by the Hiroshima device.

Table 1. Radiative Forcing Since 1800 (25-Year Intervals)

Because W/m² is an abstract measure for most audiences, scientists sometimes translate the Earth’s net heat uptake into the equivalent energy released by Hiroshima-sized atomic bombs. One Hiroshima bomb released approximately 6 × 10^13 joules of energy. While no explosions are implied, the comparison conveys the sheer scale of heat now accumulating in the Earth system.

The international discussions and assessments surrounding COP30 confirmed that earlier warming projections—particularly those assuming that the 2 °C threshold could be avoided with moderate mitigation—were too conservative. Updated analyses indicate that human-induced warming will almost certainly exceed 1.5 °C in the early 2030s. This threshold is driven not only by carbon dioxide but also by the rapid acceleration of methane and nitrous oxide concentrations, combined with the reduction of aerosol-related cooling.

Current national policies collectively place the world on a warming trajectory closer to 2.4–2.8 °C this century, with Climate Action Tracker estimating a central pathway of approximately 2.6 °C. Under high-forcing scenarios that account for the accelerating rise of methane and nitrous oxide, global warming could approach 2 °C in the 2040s–2050s.

Methane and nitrous oxide are major contributors to the acceleration of radiative forcing. Methane is approximately eighty-six times more powerful than carbon dioxide over a twenty-year period and has been rising at its fastest recorded rate. Its main sources include fossil-gas leakage, expanding tropical wetlands, waste systems and livestock production.

Nitrous oxide is roughly three hundred times more potent than carbon dioxide and is now the fastest-growing long-lived greenhouse gas, driven by synthetic fertilisers, manure and microbially active soils in a warming climate. Atmospheric nitrous oxide concentrations now exceed 335 parts per billion—a level unprecedented in hundreds of thousands of years. Despite their significance, both gases remain inadequately addressed in most national climate strategies.

Understanding these accelerating physical drivers is essential for effective nature protection. Climate disruption has become the dominant force reshaping ecosystems, altering rainfall, intensifying fire regimes, shifting species distributions, and accelerating ecological stress. Conservation approaches based on fixed ecological baselines are no longer sufficient. Effective environmental work now requires adaptive restoration strategies, expanded ecological monitoring, local community stewardship and clear communication about the biophysical forces transforming the natural world. Without this understanding, restoration efforts risk being overtaken by the speed and magnitude of climate-driven ecological change.

James Hansen’s 2025 analysis argues that radiative forcing is rising at around half a watt per square metre per decade—faster than the central projections of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. His work emphasises that the climate responds to physical forcing rather than political pledges. Under the present trajectory, Hansen suggests that 1.5 °C is effectively a passed threshold, and avoiding 2 °C would require transformative global action. He also cautions that large-scale carbon removal remains economically and technologically unrealistic at the scale required, while early resistance to nuclear energy helped lock in decades of gas expansion. Although some of his higher-end risk assessments are contested, his central message—rising forcing, a large energy imbalance and escalating risk—is widely acknowledged.

Scientific consensus on these issues is remarkably strong. Reviews of tens of thousands of peer-reviewed papers and international surveys of the publishing climate of climate scientists consistently show 97–100% agreement that climate change is real and primarily driven by human greenhouse gas emissions. Literature analyses, expert surveys, and statements from national scientific academies support these conclusions.

The physical reality of rising radiative forcing provides essential context for environmental protection and community education. It clarifies why the climate system is shifting so rapidly and why conservation must adapt to a world where the underlying conditions for ecosystems are changing year by year.

What to do when a person challenges these things.

When someone challenges these facts, the most useful response is to return to the strength of the evidence rather than the intensity of the argument. Radiative forcing is not an opinion but a directly measured physical quantity, confirmed independently by NASA, NOAA, CSIRO, and the IPCC. A calm invitation to examine long-term data—especially greenhouse gas concentrations, Earth’s measured energy imbalance, and satellite observations—helps shift the discussion away from ideology and back toward observable reality. Encouraging respectful curiosity, offering clear sources, and emphasising that scientific consensus emerges from many lines of evidence rather than political alignment can maintain psychological safety while still grounding the conversation firmly in empirical science.

Another effective strategy is to invite the person to contact the scientists or scientific organisations directly. This approach works for three simple reasons. First, it shows confidence rather than defensiveness by directing them to the highest-grade evidence available. Second, it shifts the discussion from opinion or ideology back to verifiable data, since responses from CSIRO, NOAA, BoM or academic researchers carry transparent scientific grounding. Third, it respects their autonomy by encouraging them to investigate the facts for themselves. You can then invite them to return and discuss the responses they receive, keeping the conversation open while ensuring it remains anchored in credible expertise. is to return to the strength of the evidence rather than the intensity of the argument. Radiative forcing is not an opinion but a directly measured physical quantity, confirmed independently by NASA, NOAA, CSIRO, and the IPCC. A calm invitation to examine long-term data—especially greenhouse gas concentrations, Earth’s measured energy imbalance, and satellite observations—helps shift the discussion away from ideology and back toward observable reality. Encouraging respectful curiosity, offering clear sources, and emphasising that scientific consensus emerges from many lines of evidence rather than political alignment can maintain psychological safety while still grounding the conversation firmly in empirical science. for environmental protection and community education. It clarifies why the climate system is shifting so rapidly and why conservation must adapt to a world where the underlying conditions for ecosystems are changing year by year.

References

1. Hansen J. Colorful Chart. 21 November 2025. Columbia University Earth Institute; 2025.

Climate Action Tracker. COP30 global warming projections remain stubbornly high. Climate Analytics; 2025.

World Meteorological Organization. State of the Climate Update for COP30. WMO; 2025.

Lynas M, Houlton B, Perry S. Greater than 99% consensus on human-caused climate change in the peer-reviewed scientific literature. Environ Res Lett. 2021;16(11):114005.

Cook J, Nuccitelli D, Green SA, Richardson M, Winkler B, Painting R, et al. Quantifying the consensus on anthropogenic global warming. Environ Res Lett. 2013;8(2):024024.

Powell J. Climate Scientists Virtually Unanimous: Anthropogenic Global Warming Is True. Bull Sci Technol Soc. 2019;39(2-3):67–70.

IPCC. Sixth Assessment Report: Working Group I. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; 2021.

Meinshausen M, Vogel E, Nauels A, Lorbacher K, Meinshausen N, Etheridge DM, et al. Historical greenhouse gas concentrations for climate modelling. Geosci Model Dev. 2017;10:2057–2116.

NOAA. Global Greenhouse Gas Reference Network. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; 2025.

Hansen J, Sato M, Ruedy R, Lo K, Lea DW, Medina-Elizade M. Global temperature change. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(39):14288–93.

Trenberth KE, Fasullo JT. Tracking Earth’s energy: From El Niño to global warming. Surv Geophys. 2013;33:413–26.

Glasstone S, Dolan PJ. The Effects of Nuclear Weapons. 3rd ed. U.S. Department of Defense; 1977.

CSIRO, Australian Bureau of Meteorology. State of the Climate 2024. CSIRO; 2024.